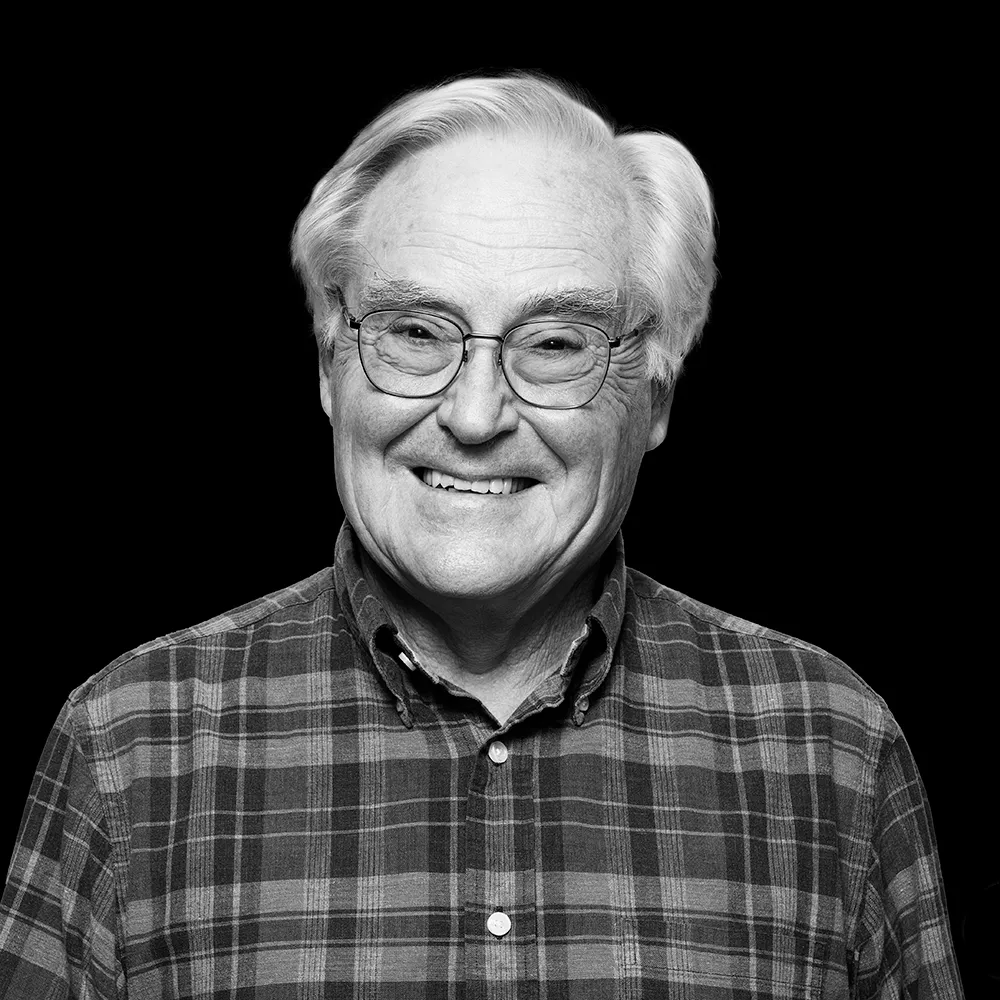

Dr. Craig Heller: Using Temperature for Performance, Brain & Body Health

Listen or watch on your favorite platforms

In this episode, Dr. Huberman is joined by Dr. Craig Heller, Professor of Biology at Stanford University and a world expert on the science of temperature regulation. They discuss how the body and brain maintain temperature under different conditions and how almost everyone uses the wrong approach to cool off or heat up. Dr. Heller teaches us the best ways and, in doing so, explains how to offset hyperthermia and hypothermia. He also explains how we can use the precise timing and location of cooling on our body to greatly enhance endurance and weight training performance. He describes how cooling technology discovered and engineered in his laboratory has led to a tripling of anaerobic (weight training) performance and allowed endurance athletes to run further and faster and eliminate delayed onset muscle soreness. Dr. Heller explains how heat impairs muscular and mental performance and how to cool the brain to reduce inflammation and enhance sleep and cognition. Dr. Huberman and Dr. Heller discuss how anyone can apply these principles for themselves, even their dogs! Their conversation includes both many practical tools and mechanistic science.

Andrew Huberman:

Welcome to the Huberman Lab podcast, where we discuss science and science-based tools for everyday life.

Andrew Huberman:

I'm Andrew Huberman and I'm a professor of neurobiology and ophthalmology at Stanford School of Medicine. Today, I have the pleasure of introducing Dr. Craig Heller as my guest on the Huberman Lab podcast. Dr. Heller is a professor of biology and neurosciences at Stanford. His laboratory works on a range of topics, including thermal regulation, Down syndrome and circadian rhythms.

Andrew Huberman:

Today, we talk about thermal regulation, how the body heats and cools itself and maintains what we call homeostasis, which is an equilibrium of processes that keeps our neurons healthy, our organs functioning well, and, as Dr. Heller teaches us, thermal regulation can be leveraged in order to greatly increase our performance in athletics, and mental performance, as well. Learning to control your core body temperature is one of the most, if not the most, powerful thing that you can do to optimize mental and physical performance, regardless of the environment that you're in.

Andrew Huberman:

He also dispels many common myths about heating and cooling the body, including the idea that putting a cold pack on your head or neck is the optimal way to cool down quickly. And in fact, as Dr. Heller tells us, it actually can be counterproductive and lead to hyperthermia. It's a fascinating conversation from which I learned a tremendous amount of new information, and we didn't even get into the other incredibly interesting work that Dr. Heller does on Down syndrome and circadian rhythms and sleep, so we hope to have him back in the future to discuss those topics.

Andrew Huberman:

As you'll soon see, Dr. Heller is a wealth of knowledge on all things human physiology, biology and human performance. It's no surprise then that he's been Chair of the Biology Department at Stanford for many years, as well as Director of the Human Biology program. So, if you're interested in human biology and how to improve your performance in any context or setting, athletic or otherwise, I think you'll very much enjoy today's conversation.

Andrew Huberman:

Before we begin, I'd like to emphasize that this podcast is separate from my teaching and research roles at Stanford. It is, however, part of my desire and effort to bring zero-cost-to-consumer information about science and science-related tools to the general public. In keeping with that theme, I'd like to thank the sponsors of today's podcast. And now for my discussion with Dr. Craig Heller.

Andrew Huberman:

Great to have you here.

Craig Heller:

It's good to be here.

Andrew Huberman:

It's been a long time coming. I know that I and many people have a lot of questions about the use of cold. One of the things that's happened in recent years is that, for many reasons, people have become interested in things like taking cold showers and taking ice baths for many different purposes. Sometimes this is introduced as just a general health tonic, but other times people get specific about how it can improve resilience or it can improve one's metabolism. Could you just tell me a little bit about what happens when I get into a cold shower or an ice bath? What are some of the basic responses at the level of metabolism, obviously psychologically we don't know exactly, it'll vary from person to person, but what happens when I submerge myself into an ice bath if I've never done it before?

Craig Heller:

Well, first of all, you'd get a tremendous shock, and what that's going to translate into is a bit of a shot of adrenaline. I think this is really the so-called benefit, but I wouldn't call it a benefit, of the cryo chambers. You go into a cryo chamber and it's a shock, so you get a shot of adrenaline. So sure, you're going to feel different when you come out. You've had a shot of adrenaline, but it doesn't necessarily translate into any benefit in terms of your physiology or performance and so forth.

Craig Heller:

Now, if you take a cold bath or a cold shower, a couple things are happening. One is you're going to stimulate vasoconstriction. So, if anything, it's going to make it a little bit more difficult for your body to get rid of heat because you're shutting off your avenues of heat loss. If you're in a true cold bath, the overall surface area of your body is so great that it doesn't matter if you're vasoconstricted, you're still going to lose heat.

Andrew Huberman:

Okay, so vasoconstriction, the constriction of — is it capillaries, vessels and arteries all constrict, or just one or two?

Craig Heller:

Well, this is an area of controversy. In general, when people talk of vasoconstriction, they talk of the overall skin surface. That is not true. The primary sites of heat loss, which we're going to get into, are the palms of your hands, the soles of your feet and the upper part of your face. The reason these are avenues for heat loss is they're underlain by special blood vessels, and these blood vessels are able to shunt the blood from the arteries, which are coming from the heart, directly to the veins, which are returning to the heart, and bypassing the capillaries, which are the nutritive vessels, but high resistance. You can tell when you shake someone's hand what his or her thermal status is, the hand's hot or it's cold. That's it.

Andrew Huberman:

Do you think that's part of the reason why humans evolved this practice of shaking hands, assessing each other's level of anxiety? We all know that a limp handshake is pretty indicative of something, and a firm handshake is indicative of something, as is the crushing handshake, for that matter.

Craig Heller:

Yeah, I really don't know what the evolutionary origin of hand shaking is other than to get your hand away from your weapon, perhaps.

Andrew Huberman:

Right. A couple of questions before we get into these specialized vascular compartments on the soles, the palms and the upper face. You mentioned whole-body immersion, like into an ice bath or very cold water up to the neck, versus a cold shower. Is there something fundamentally different about those two besides the fact that they both provide this release of adrenaline? Is there anything that's really important to understand about the difference in the physiological response evoked by cold shower versus immersion in cold?

Craig Heller:

Well, there are differences that are more physical than anything else. If you are in a cold bath and you're still, you develop a boundary layer. If you're in a shower, you can't develop a boundary layer.

Andrew Huberman:

Could you explain what a boundary layer is?

Craig Heller:

Yes. It's best to explain it in terms of a hot bath, because everybody's experienced that. You get into a hot bath and, oh my God, it's really hot, almost painful. And then you sit down and eventually it doesn't feel so hot anymore, because the still water, which is close to your skin, is coming into equilibrium with your skin. It's like having a blanket on you or an insulator on you. Then if you move around, you disturb that still water layer, you feel the hot temperature again.

Andrew Huberman:

I see. If I were to get into a cold ice bath or a very cold body of water of some kind and stay still, I'd likely feel warmer. At least until I start-

Craig Heller:

You're not going to be losing as much heat. Right.

Andrew Huberman:

I see. And then when I move-

Craig Heller:

If you flail around, then you're going to lose more heat.

Andrew Huberman:

Got it.

Craig Heller:

Yeah. But I think getting back to your original question about benefits; you have to keep in mind, whether you're talking about aerobic activity or anaerobic activity, if you're referring to performance and exercise and so forth. If you're doing aerobic activity that you can sustain for a long time, your production of heat is rising gradually and is being distributed throughout your body, so eventually your body temperature's going to come up to a level that's going to impair your performance. The benefit of a cold bath or a cold shower before aerobic activity is that you increase the capacity of your body mass to absorb that excess heat.

Andrew Huberman:

I see. Could you say in a rough sense that a protocol that one might use if they're going to head out for a long run, even on a reasonably warm day, not super hot, or maybe it is super hot, would be to take a cool shower before they go run? Would that be beneficial?

Craig Heller:

Sure. It'll take them longer to get to the sweat point and to heat up.

Andrew Huberman:

What will that translate to in terms of a performance-

Craig Heller:

Well, could increase your speed, or it depends on how you use that benefit. Some people are pacers, they will go at the same pace and then they will go farther, or some people are, I want to say pacers and regulators. No, pacers or forcers; they will take that advantage and use it up as fast as they can, so they will go faster, but not necessarily farther.

Andrew Huberman:

I see. As far as I know, not many athletes, at least not the ones that I know, are getting into cool bodies of water or taking cold showers before they head out to train, but it sounds like there could be a real performance benefit there.

Craig Heller:

It could be a benefit. I know we're going to talk about our technology for cooling, but at one point, I don't know if they're using it now, but our cross-country team, when they would go to compete in a very hot place, they would do their warm-up exercises, their stretching, then they would extract heat before the beginning of the race. I like to think of it as you have greater scope for heat absorption.

Andrew Huberman:

Interesting. About how long would one need to take one of these showers or cold immersions before heading out for a run? Roughly speaking, we don't have to get into details, because everyone's performance level and regimen is going to be different, where they live is going to be different, et cetera.

Craig Heller:

Right. It's not as long as you think. It's minutes.

Andrew Huberman:

A couple minutes?

Craig Heller:

Yeah. Because what's going to happen is as your core temperature goes down, you will eventually shut off your heat loss, and that keeps it from going below normal. If you're warmed up and your temperature has risen by half a degree, let's say, it doesn't take more than a few minutes to extract that heat if you're vasodilated.

Andrew Huberman:

Interesting. What about for the anaerobic athlete, the strength athlete?

Craig Heller:

Right, for the anaerobic athlete, and let's say they're doing several sets and how many reps, whatever they're doing, their core temperature's not going to rise that fast, because it's only certain muscles which are being used, but the temperature of those muscles will go up.

Andrew Huberman:

So it's a local effect?

Craig Heller:

It's a local effect. Right.

Andrew Huberman:

Okay. Let's say for sake of today, maybe for this discussion, if we assume that the basic workout, even though people do a variation on this, is five sets of five or 10 sets of 10. For those listening, it would be five sets of five repetitions, or 10 sets of 10 repetitions, 10 by 10, five by five. Yeah. If somebody, let's say, is doing a large-body compound movement like barbell squats, where there are a lot of large-body movements, hip hinging, et cetera, but for instance, the biceps, they're involved, but more or less indirectly. The effect is going to be to heat up the quadriceps, heat up the ham strings, heat up the glutes, this kind of thing?

Craig Heller:

Right.

Andrew Huberman:

I see.

Craig Heller:

And then during rest, that heat will leave the muscle, but it's not fast. Certainly, the heat can't leave the muscle very fast while you're working out because when the muscle contracts, it squeezes the blood vessels. The only way heat gets out of a muscle is in the blood, and your muscle metabolism can go up 50- or 60-fold during anaerobic activity. That means the heat production in the muscle goes up 50- or 60-fold. The blood flow to that muscle cannot go up 50- or 60-fold, so you literally have the capacity to cook your muscles.

Andrew Huberman:

This is probably an appropriate time to just mention briefly what the underlying mechanism of this is. Could you just? We will return to the specifics of what one can do to mitigate this heating up, but could you just explain the relationship between energy production, ATP and pyruvate kinase, and the role of heat there?

Craig Heller:

Sure. We don't get something for nothing. Like a steam engine, most of the energy in our food is lost as heat. We are roughly about 20% efficient, so of the energy that we take in in our food, about 20% of that can go into doing work and the rest of it is lost is heat. Now, we're mammals. We use that heat to keep our body temperature considerably above the environment, but if you raise body temperature a few degrees higher, you're in trouble. That's hyperthermia. Individual muscles can reach hyperthermic limits before you might experience it in the whole body.

Craig Heller:

To keep you from damaging your muscle by hypothermia, we have fail-safe mechanisms. One of those fail-safe mechanisms is an enzyme which is critical for getting fuel, in other words the results of metabolism, of glucose, getting that fuel into the mitochondria, which is making our major coinage of energy exchange, ATP. That particular enzyme is temperature sensitive, so when the muscle temperature gets above 39 or 39.5, it shuts off. That essentially shuts off the fuel supply to the mitochondria. That's when you cannot do one more rep.

Andrew Huberman:

Failure.

Craig Heller:

Muscle failure.

Andrew Huberman:

Could we say that one component of muscular failure is overheating of the muscle locally. There are probably other things, too.

Craig Heller:

Right. Well, if you lack oxygen, but our oxygen delivery is pretty good to the muscle. If you run out of glucose, yeah, that's going to impair you. But the most immediate, the most immediate impairment of muscle activity, muscle fatigue in other words, is the rise in temperature of the muscle.

Andrew Huberman:

Interesting. I want to talk about how that muscle fails locally, but I have this burning question in my mind that I cannot seem to answer for myself. I'm hoping you can answer it for me. Let's say I'm doing five sets of five with squats. I hit muscular failure at a given weight. And according to what I now know, it's my quadriceps and the muscles associated with the squat that have failed because of this heat, triggering this mechanism, triggered by heat that shuts off the muscle. But my biceps are nice and cool, you're telling me. They're not doing too much work. It's only indirect work. So why is it that I can't set the bar down in the squat rack, walk over and do barbell curls with the same intensity that I could if I were to do those barbell curls fresh, not having done anything prior?

Craig Heller:

Well, you will still have a fatigue curve with your upper body, and that will be influenced by any rise in temperature that has been generated by your lower body exercise.

Andrew Huberman:

So, temperature in both cases is the limiting factor?

Craig Heller:

It's one limiting factor. It's one limiting factor.

Andrew Huberman:

I find that amazing. I find that amazing, because I always thought, naively, that the reason muscles fail is because we, quote, don't have the strength to do another repetition, or it's that you lack glycogen or some ability to access that glycogen. But of course we still have glycogen. It's naive for me to think that, because if I wait three minutes and go back, I can do those repetitions again, so the glycogen wasn't restored in that three minutes. Obviously it was there. I realize there might be other mechanisms involved. It sounds like heat is, if not the dominant mechanism that prevents more work, it's one of them.

Craig Heller:

It's one of them, and it's a quick one. It's a fast one. It can happen with, let's say you are a really experienced weightlifter. Okay? You may be doing very, very high weights with sets of five or six.

Andrew Huberman:

To be clear for the audience, I'm not doing very high weights with sets of five. I'm not particularly strong. I'm not super weak, but I'm not particularly strong, but Craig's referring in the general sense to you.

Andrew Huberman:

Why is it that if I finish a set of squats, I can't simply cool off my quadriceps by throwing a nice cool towel on my quadriceps? Why is that not the best way to go about it?

Craig Heller:

Because your body surface is a very good insulator. Okay? We think we don't have fur and therefore we're not insulated, but the skin, the fascia, the muscles underneath, they're all very good insulators. That's why I said earlier that the way the heat gets out of the muscle is in the blood.

Andrew Huberman:

I want to step through a couple other portals by which one might think that heating and cooling would be ideal and then get back to these specialized surfaces on the hands, the feet and the face.

Andrew Huberman:

If throwing a cold towel or even ice-cold towel on my quadriceps isn't going to work, or standing in front of the fan, because I'm insulated from that cool. I can't cool off my blood fast enough. What about drinking 16 ounces of ice water?

Craig Heller:

Sure, you can do that, but you can calculate how much heat that can absorb. And you can't continue drinking liters of ice water. You're going to dilute your blood and have other problems. But yes, it'll help. Sure, it will help. But it doesn't have the full capacity you will need.

Andrew Huberman:

What about an ice pack to the back of my neck or to my head or squeezing the cold sponge over the head? I'm deliberately moving through these options because these are the ones that we see most often. We were actually just watching the Olympic track and field trials last night up in Oregon. I'm a huge track and field fan, and there were a lot of sponges on the backs of necks before and between and after events. How good is that or how poor is that as a strategy, since now we know that being overheated locally and systemically throughout the body is a serious limiting factor on performance?

Craig Heller:

Well, you have to understand something about our thermal regulatory system. We have a thermostat, just like you have a thermostat in your house, and that thermostat is in the brain. Okay?

Andrew Huberman:

Do we know the specific site? Yes.

Craig Heller:

Yes. It's called the preoptic anterior hypothalamus. It does many things in terms of physiological regulation, but it serves as a thermostat. Now, that thermostat has to have information, it has to have input. Where does that input come from? It comes from our overall body surface, where we sense temperature. Okay? One of the things that can happen when you're overheated is that you can send in a cold stimulus to your thermostat, and that's sort of like wanting to cool your house by putting a wet washcloth over your thermostat. It's doing the wrong thing. We've actually had experiences where we've had people exercising, getting overheated and then cooling the body surface. They say, "It feels great. This is fantastic." And their core temperature is going up.

Andrew Huberman:

I think this is such an important point. First of all, I was weaned in a laboratory where there were always battles over the temperature in the lab. People were always putting ice packs on thermostats or putting fans towards thermostats and trying to play this game. Good to know we were all being foolish, even though we were neurobiologists. Putting a cold towel over my torso, or putting ice on my upper back, you're saying could actually heat up my core?

Craig Heller:

It'll at least decrease your heat loss, your rate of heat loss. You're going to raise the issue a little later, I know, and that is our natural portals for heat loss. You can think of the natural portals for heat loss as our air conditioners. Okay? The thermostat's in the brain, and the information to the thermostat is coming from the overall body surface. What can happen if you, let's say, cool the torso with an ice vest, you can actually cause vasoconstriction of your portals, your heat loss portals. That's what impairs the rate at which you're losing. It feels good.

Craig Heller:

Now, back to the head, that's really interesting. The major blood flow to the brain comes up four arteries through the neck. There's the carotid arteries and there's the vertebral arteries. So when you put a cold towel around the neck, you are going to be putting a cold stimulus into the brain. Well, that's great for protecting the brain, you want to protect the brain, but it's also going to make you feel cooler than you are. You will think you're ready to go again quickly when you've just essentially cooled the thermostat.

Andrew Huberman:

This is an important point. There's a lot of interest nowadays in people doing marathons, and there are even some people do these ultras, ultra running, which I guess is everything longer than a marathon, and go last man standing — last man, last woman — standing kind of things. You're saying that if somebody's hyperthermic, they could trick themselves into subjectively thinking that they are cooling off by putting on a towel, and that they can go further, but their brain could cook.

Craig Heller:

That they could go further? Well, if they stop the cooling, then that hot blood from the body core is going to go to the brain.

Andrew Huberman:

Interesting. Well, It's a bit of a tangent, but many people report after long bouts of exercise, or even just very intense bouts of exercise, feeling a kind of brain fog or mental fatigue. I assumed that that was due to lowered brain oxygenation postexercise, but is it possible that there is some postexercise effects on heating and cooling of the brain that might impact cognition, or I should say negatively impact cognition?

Craig Heller:

It's certainly possible, because we know that a rise temperature decreases cognitive capacity. I mean, you can experience that yourself. You can get on a treadmill and follow your temperature and then just do a simple activity like adding and subtracting. You get to about 39 degrees, you can't do that anymore. You can't just calculate how long you've been on the treadmill.

Andrew Huberman:

So, the phrase "cool, calm and collected" is — that's the goal in all pursuits.

Craig Heller:

Cool, calm, and collected, that's right.

Andrew Huberman:

I want to talk about these portals because you've mentioned them a few times. Before I ask about what the portals are exactly and how they work and how they can be leveraged for performance, just there's a question that my neurobiologist self can't resist but ask. We have this thermostat in the preoptic area of the hypothalamus. Which is interesting to me, the medial preoptic area is also one that's known to be sexually dimorphic, depending on testosterone exposure early in life, et cetera. Although people should just note that it's not actually testosterone that creates these sexual dimorphisms, these differences, it's actually testosterone converted into estrogen. It's actually, estrogen is the effector, which is fascinating.

Andrew Huberman:

Nonetheless, we've got this area that acts as a thermostat. You said it's collecting information from the whole body. Does that mean that there are pathways, as the neuroscientists like you and I refer to them as these afferent or input pathways from the body to the preoptic area? Is there a map of our body in the preoptic area? I have to imagine that you can't have the information just coming from the left shoulder, just from the right toe. It sounds like you need probably a pretty crude map, but that you need a complete map of the body surface there.

Craig Heller:

Well, you don't need a complete map in the hypothalamus. I mean, that thermal afferent information that you've mentioned, it also goes to the somatosensory cortex. You know if an ice cube has touched you on the back, but that doesn't necessarily translate into a change in, let's say you're shivering or sweating. The information that's going to the hypothalamus is a more integrated representation of body temperature.

Andrew Huberman:

It's sort of an average of what's happening across the body?

Craig Heller:

It's an average.

Andrew Huberman:

If I were to, let's say I get hot on a hot day, and popsicles, when you're in summer camp. I went to a sports camp, here actually, and we'd run around crazy and then we get into the shade if we could, but we were — popsicles. It was all about popsicles.

Craig Heller:

Brain freeze.

Andrew Huberman:

Or the kids were putting ice cubes down each other's shirts or something. But that's an average because other parts of the body aren't exposed. The mouth is exposed to the ice in the popsicle case, or the cold cubes are in the hands. As you said, it feels really good.

Craig Heller:

It feels good, yeah.

Andrew Huberman:

But it sounds like it feels deceptively good, because in reality, you could still be quite warm internally.

Craig Heller:

Absolutely, yeah.

Andrew Huberman:

Interesting.

Craig Heller:

Yeah, you can feel great and have a dangerously hyperthermic temperature. But I should say that when you get into the danger zone, things get bad fast.

Andrew Huberman:

What are some of the symptoms that people could be on the lookout for, for hyperthermia?

Craig Heller:

Essentially, it's almost ironic that if individuals are transitioning into heatstroke, they actually vasoconstrict and they stop sweating. That's a pathological situation. I couldn't begin to explain it. But essentially, you are just feeling exhausted. You're feeling miserable. The heart rate is very high. Your heart rate goes up as your core temperature goes up. It's called cardiac drift. You just feel rotten. But that's why, since it's not a dangerous signal that you can translate immediately into, "Nope, I'm going into heat stroke," that's why people can overcome their bad-

Craig Heller:

I'm going into heatstroke. That's why people can overcome their bad feeling with motivation to continue going to work harder. So there have been a number of high profile athletic deaths due to heatstroke that were during practice. Not in competition when people are really trying to do it, but in practice, which shows they were just motivated to push.

PART 1 OF 4 ENDS [00:27:04]

Andrew Huberman:

So let's talk about these magnificent portals that not just humans but other animals, mammals, are equipped with. So if putting cold on the neck or on the head or on the torso is not optimal, what is optimal? And maybe walk us through a theory as to why we would have these portals located where they are and then we can talk about how one might leverage them for performance.

Craig Heller:

Okay. Where the portals are are in the glabrous skin. Big word. Okay. Glabrous just means no hair. So it's the hairless skin. You say, well, most of my body is without hair. No. Most of your body has hair follicles. We are mammals. Mammals have fur. We've lost the fur, but we still have that hairy skin phenotype all over our body, except for those skin surfaces where our mammal relatives didn't have fur. So the pads of the feet and for the primates, upper part of the face. For rabbits, no portions of the ears. The inner surface of the ears.

Andrew Huberman:

I never thought about that.

Craig Heller:

For bears, the tongue. Bears have big tongues, huge tongues.

Andrew Huberman:

I didn't know that either. Haven't been that close to a bear yet.

Craig Heller:

Haven't had a licking match with a bear.

Andrew Huberman:

Not yet, no.

Craig Heller:

So anyway, our mammalian relatives can't lose heat over their overall body surface. So probably very early on in mammalian evolution, they evolved these special blood vessels in the limited surface areas that don't have fur. And as I said, what these blood vessels are are shunts between the arteries and the veins. Arteries and veins are both low-resistance vessels so you can have high flow rate. Capillaries, which normally are between arteries and veins, are high resistance because they're very tiny. Okay.

Andrew Huberman:

Is it fair to say that what I was taught is that blood flows from arteries then to capillaries and then to veins and then back to the heart?

Craig Heller:

Yes.

Andrew Huberman:

So it's like from the heart through arteries, then through these little capillaries, which are little estuaries and streams, and then to the veins back to the heart. Is that generally true?

Craig Heller:

Right. Yeah. Absolutely.

Andrew Huberman:

Okay. So what I learned in basic physiology is still ... I wouldn't get an F in your class.

Craig Heller:

No.

Andrew Huberman:

Okay. Maybe a D or a C, but not an F.

Craig Heller:

So that's excellent.

Andrew Huberman:

Okay. And so you're saying that in this glabrous, or beneath the glabrous skin ...

Craig Heller:

There are these shunts.

Andrew Huberman:

And those go directly from arteries to veins.

Craig Heller:

Right.

Andrew Huberman:

So you skip the capillaries.

Craig Heller:

Capillaries, yeah.

Andrew Huberman:

Is it actually, as long as I say that in the skin, when I feel the pads in my hands, how deep to the surface do these vessels reside?

Craig Heller:

Well, they're below, obviously, the epidermis. So if you are warm and you look at your palms or your hands, they are fairly red. The backs of your hands aren't. You don't have these vessels in the backs of your hands. Now if you take a glass, like a water tumbler, and you grab it, you can see if you squeeze a little bit, the hand goes white. That's because you've shut off that blood flow.

Andrew Huberman:

Oh, interesting. I'm going to do that little home experiment.

Craig Heller:

So if you're bicycling on a hot day, you don't want to be grabbing your handlebars all the time. You want to periodically.

Andrew Huberman:

Well, this is important. I know you're privy to some really amazing results that we're going to talk about. But I actually heard you say this during this lecture recently that Stanford held about human performance that we were both part of. And you mentioned this, that if you're cycling and you're working hard and you want to be able to do more work, we now know why you want to remain cool, in order to continue to do work. And if you get too warm, that's bad. That gripping the handlebars too tightly will actually limit your performance.

Craig Heller:

Right.

Andrew Huberman:

And that's probably also true on the Peloton or any other kind of device, or the skier or anything like that. So loosen the grip or if you safely can; you want to actually expose your hands right to the world. Now what about for people wearing gloves? To me, that just seems crazy based on everything you're telling me.

Craig Heller:

Well, gloves definitely impede heat loss from the hands, just as socks impede heat loss from the feet. Okay. So if you want to maximize your heat loss, you want to have as thin protectors as possible on your hands. And of course the feet are more problematical because you have to be using them in certain ways.

Andrew Huberman:

Some people run barefoot.

Craig Heller:

Yeah. Well, yeah.

Andrew Huberman:

Yeah. That's become somewhat popular. It seems like it came and went. They had those toe shoes things, but they looked so ridiculous that I think most people just were willing to take the performance hindrance of regular shoes.

Craig Heller:

Actually, we had a track coach here at Stanford who, for a while, was famous for introducing training without shoes. Running.

Andrew Huberman:

Interesting.

Craig Heller:

And he thought it was because it changed the posture of the runner. And I think it was just due to the fact that he was increasing the capacity of his runners to lose heat.

Andrew Huberman:

Interesting. So heating up at the level of the hands, obviously, is going to hinder performance. So if I can, how about with running? I noticed — I ran cross-country briefly in high school, and not particularly well at that, but that we were told to run as if we were holding crackers in our fingers, or something, like very lightly and to keep hands loose. So running like this would actually be more beneficial for performance than, or gripping a phone, which is probably what most people are doing nowadays. Right. Interesting.

Craig Heller:

Once, I'll tell you an experience I had once. I was in Alaska in the winter, and I went out running and I absentmindedly forgot gloves. And I realized this after a short period running because the backs of my hands were aching from the cold, the palms of my hands were sweating and were hot.

Andrew Huberman:

Oh, amazing. Amazing. So these compartments are a real thing. And you mentioned the upper half of the face.

Craig Heller:

The upper part. That's where our primate ancestors don't have fur.

Andrew Huberman:

And the bottoms of our feet. So let's just take a moment, talk about some of the more amazing results that have been associated with proper cooling of these glabrous skin surfaces.

Craig Heller:

Let me introduce one more thing.

Andrew Huberman:

Sure.

Craig Heller:

Because you asked earlier about the pouring of water on the head. One of the things which is not appreciated fully is that the blood, which is perfusing these special blood vessels in the face, above the beard line — that's the nonhairy skin. That blood then returns in the venous supply to the heart. But it actually does it in a very strange way. It actually goes through what are called; I'm blocking on the name now.

Andrew Huberman:

Take your time.

Craig Heller:

These are blood vessels. They go through the skull, and that's why the scalp bleeds a lot if you cut the scalp. And these blood vessels, which are called, I want to say emergent, but it's not emergent. It's a word that means leaving. And these blood vessels were primarily thought to be ways that blood is leaving the brain. But when you're overheated, the direction of flow in those blood vessels reverses. So the cooled blood that's coming from your facial region goes into that circulation and actually is a cooling source for the brain. So you can cool the brain, you can have a cooling effect on the brain by pouring water on your head.

Andrew Huberman:

Interesting. So that practice, which we — at least for me, I most commonly associate with combat sports. Where someone, the fighter goes to their corner, they usually sit down on a stool unless they're trying to do some mental warfare from the corner, in which case they don't even take a seat. And their corner crew will squeeze a sponge full of cold water over them. That you're saying is somewhat effective in cooling the brain.

Craig Heller:

Yeah. It's one of the natural mechanisms for cooling the brain.

Andrew Huberman:

I want to return to this at some point, as well, but is there any known benefit to cooling the brain, in terms of offsetting physical damage, offsetting the negative effects of concussion? Because one of the reasons why fighters will often get a cold item on the back of the neck, or on the head, is not just to cool them down, but the theory is that it might offset some of the damage of neurons.

Craig Heller:

I just can't comment on that. I'm aware of those ideas, but they're controversial. One of the things that you want to do for injury to the brain is to decrease swelling. And one of the ways that you decrease swelling in many parts of the body is to cool. It decreases inflammation, it decreases the blood flow. So I think it's a really interesting topic, and it's something that should be investigated. It's hard to investigate.

Andrew Huberman:

Yeah. Interesting. Okay. So I hear these stories and I've seen the data, so I believe the stories. Maybe tell us a story about an observation that your group has made with respect to anaerobic exercise and proper cooling of these glabrous surfaces. And we can talk about the technology. Maybe give us the dips example first. Dips, of course I think most people are familiar with dips. You're supposed to get down-

Craig Heller:

Raise and lower your body mass.

Andrew Huberman:

Yeah. Raise and lower body mass, usually with your legs dangling down. Sometimes people strong enough to attach a weight there and they'll do, it's essentially a compound upper-body exercise. One dip would not be particularly impressive for most people. A hundred would be very impressive, 20 would be impressive for some, et cetera. What happens when a skilled athlete comes in and does dips for multiple sets? And then what happens when they cool properly using the glabrous skin surfaces?

Craig Heller:

This was a story that occurred early on in our investigations when we first made the discoveries that cooling has a benefit to increase your work volume, your capacity to do more reps. So the word got over, I think, to the 49ers camp, and one of their players, Greg Clark, who was a tight end at the time — he had been tight end at Stanford — he decided, or I don't know if he was asked or what, to come over and check it out. So Greg came over and we said, "Greg, what are you good at? What activity do you like to do?" He said, "Dips, I can do a lot of dips. I can do 40 dips in a first set, and I can probably do five sets. That's a usual workout for me." And we said, "Okay." So he came over to the gym one day, and that's exactly what he did. He did 40 dips the first set, and then maybe 25 and 15, and down from there.

Andrew Huberman:

Do you recall roughly what kind of rest periods he was taking between sets?

Craig Heller:

Yeah, we standardized the rest period to three minutes, because that's what we had set on for cooling as the [inaudible 00:39:20]

Andrew Huberman:

That's a good, long rest period.

Craig Heller:

Yeah, it is.

Andrew Huberman:

It's still a lot of dips.

Craig Heller:

Yeah, it's actually a longer rest period than many people would prefer during workouts. They want to make the most of their time.

Andrew Huberman:

Not me, I prefer to take as much rest as I possibly can.

Craig Heller:

So several days later, he came back and his first set, he did, I think maybe 42, a little bit better. But now people were standing around watching, so there was a little impetus there to show off. So then his second set was, I don't remember the numbers, but very much above the second set on the control day. This was after we cooled his palmar surface.

Andrew Huberman:

When is he doing the cooling?

Craig Heller:

He's sitting down and putting his hands in the devices that we had built, which were cooling the palms of his hands.

Andrew Huberman:

For how long does that cooling take? Can he do it inside of a three-minute rest period?

Craig Heller:

Yeah, that's what we were doing.

Andrew Huberman:

Yeah.

Craig Heller:

We standardized the interval for resting or cooling to three minutes. But the point is, he got to his fifth set, and all of the sets were above what he had done on the previous day. And he said, "I'm not tired. I can do another set, and then I can do another set. I can do another set, I can do another set." So from one day to two or three days later, with cooling, he doubled the total work volume. He doubled the total number of dips

Andrew Huberman:

By adding more sets and more repetitions to each set.

Craig Heller:

Right. So then he kept coming back for four more weeks, twice a week. And by the end of that month, he was doing 300 dips.

Andrew Huberman:

Wow, so what percentage?

Craig Heller:

So he tripled. He essentially tripled. And so here's a professional athlete at peak physical conditioning, and he triples what he can do.

Andrew Huberman:

Amazing. Amazing. And in terms of his ability to recover, was that explored or discussed at all? Because my understanding is that if we cause enough stress to a muscle during anaerobic training, we provide the stimulus for compensatory regrowth, et cetera.

Craig Heller:

Right, Right.

Andrew Huberman:

But if we do more work, we essentially scale up the amount of recovery that's needed, or the recovery time. I'm very curious about whether or not he needed longer to recover between these superperforming workouts.

Craig Heller:

That's very interesting. That was a major discovery, which we didn't realize we were making at the time. There is this phenomenon you're referring to as delayed onset muscle soreness, DOMS. And this is due to those little microtears, and so forth, that are happening as we extend our workout capacity — volume. So we've had this experience so many times that an athlete or anyone will come into the lab, and they will exceed what their previous goals were, their previous expectations. And I can always see the words coming out of their mouth, "I'm going to be so sore tomorrow." They never are.

Andrew Huberman:

Interesting.

Craig Heller:

And we've actually demonstrated that with a naive group. We had a class, a physical conditioning class, and we had half of them ... The first days of the class, we had to establish their true capacity, what they could do. So these were pretty heavy workouts for these new recruits. And we gave half of them the benefit of cooling and the other half not. And then we had them record their subjective levels of delayed onset muscle soreness. And those that were cooled didn't have significant muscle soreness.

Andrew Huberman:

Amazing. And I know there are also published results, and we will provide links to some of these papers for people, seeing similar effects, I should say, similar performance-enhancing effects using bench presses. Bench press or pushups or other sorts of things. Maybe you could give us an example from the realm of endurance work or aerobic work. Running, cycling, things of that sort.

Craig Heller:

Well, one of the problems for us is that our equipment now is not really portable. I mean, it's portable in the sense you can carry it to the gym or to the football field-

Andrew Huberman:

But you're not going to run with it.

Craig Heller:

But you're not going to run with it.

Andrew Huberman:

Right. Or equip a bicycle with it. Although when are the cooling handles on bicycles coming?

Craig Heller:

That would be good, but one itinerant activity is golfing, and people have put it on their golf carts and they're out.

Andrew Huberman:

Do people really heat up that much in golf?

Craig Heller:

They do.

Andrew Huberman:

Not to be disparaging of the golfers, but the way I conceptualize golf, it's like a swing and then a walk and then a cart ride and then a meal. I probably just offended all the golfers out there.

Craig Heller:

One time we had, we were doing work for the Department of Defense, and they wanted to check it out. Whether or not what we were doing was really worthwhile. So they sent out a team of special ops soldiers to be our subjects and test it out. They were here for a week. So that was a fun week.

Andrew Huberman:

Yeah. I do some work with those guys. They're hard-driving guys. They also know how to have fun, but definitely have, if they have an off or a quit switch, it's buried deep within their nervous system. They don't like to hit that quit switch.

Craig Heller:

So the guy who wrote the final report, he gave an addendum to the report and he said, "Well, I'll tell you this, after I've gotten home, it's added ..." They took the technology with them, they wanted to keep it.

Andrew Huberman:

Yeah. That sounds about right.

Craig Heller:

"And using it has added 20 yards to every club in my bag. And that's no effing small deal."

Andrew Huberman:

Wow. So it's allowing people to hit further, hit the golf ball further.

Craig Heller:

Right.

Andrew Huberman:

Interesting. All right. So for the golf players out there, then that's the reward you get back from Craig for all my little knocks on golf. I actually, I don't have any knock on golf. I just don't think about it as a sport where heating up is a limiting factor. So since they're getting more out of their drive, what do you think is going on there?

Craig Heller:

Well, they can be heating up and [inaudible 00:45:44]

Andrew Huberman:

They were wearing gloves, right?

Craig Heller:

Right. On a hot day and so forth. But let just tell you one more serious story about golfers, and that is individuals with multiple sclerosis are exceedingly temperature sensitive.

Andrew Huberman:

I didn't know that.

Craig Heller:

So they may still be mobile, but they have to stay in cool locations and not increase their exercise to any great extent. But we've had subjects with multiple sclerosis who have just essentially put the device on their golf cart, and they're back out playing golf in the middle of the summer.

Andrew Huberman:

Oh, that's great. That's great. Anything that allows people to have normal levels of livelihood and recreation is great. We always think about performance at these peak and elite levels and pushing harder. But anything that allows people to be mobile and functional is great. So what's your favorite example of endurance? And feel free to give us the extreme one, and then we'll talk about averages to make sure we're thorough about averages versus exceptions.

Craig Heller:

We haven't done a lot in the field. I mean outdoors. Most of our endurance has been in a hot room with treadmill work, and so forth. So the very first experiment, we had, I think, maybe 18 subjects just off the street. We just recruited people in the hallways. Come on in and do this. And what we found is we could, for this group with one trial with and without cooling, we could double their endurance walking on the treadmill, walking uphill on the treadmill in the heat, like maybe 40 degrees, ambient temperature, 40 degrees centigrade.

Andrew Huberman:

So what does that experiment look like? You're having people walk on an incline; it's really warm. Some people are just going to hit the quit button and say, "I've had enough" and get off the treadmill.

Craig Heller:

Right.

Andrew Huberman:

With proper cooling, when are they doing the cooling?

Craig Heller:

They're doing it continuously.

Andrew Huberman:

I see.

Craig Heller:

Because in the laboratory we can suspend devices from the ceiling, for example.

Andrew Huberman:

Sure.

Craig Heller:

Now we do have prototype wearable devices. We did them in response to emails from Ebola workers a number of years ago in Sierra Leone. They said, "We've read about your work with athletes. Can't you do something for us? We're in the personal protective gear and we can't be in the hot zone for more than 15 or 20 minutes." So that started us on the challenge of developing wearable systems that could go under the PPE. We've published that work now [inaudible 00:48:17]

Andrew Huberman:

That's great. I'm guessing the military special operators that are out in the desert and other locations are probably excited about this technology.

Craig Heller:

Well, once they get it.

Andrew Huberman:

Once they get. It's coming. It's coming. I think some people might wonder, if there are all these studies and there are these incredible results over the years, why haven't we heard more about it? And I will ask your opinion on that as well, but I'll just editorialize a little bit. The best laboratory work and its practical applications oftentimes requires many studies, and oftentimes there isn't a portal, so to speak, to get that information out into the technology sector. So there is a company that's developing this technology for people to use.

Craig Heller:

Right.

Andrew Huberman:

To purchase and use. You might as well just tell us now. What is the name of that company, and do they have a website? People are going to want to know where can they get this magical technology, and is there a poor man's version of it as well?

Craig Heller:

Well, the company's Arteria, A-R-T-E-R-I-A, and the website is www.coolmitt.com. So COOLMITT is just C-O-O-L-M-I-T-T.

Andrew Huberman:

Yeah.

Craig Heller:

Coolmitt.com.

Andrew Huberman:

It's a great website. When I went there, it says that right now the technology is only available to professional sports teams and military. Is that true?

Craig Heller:

Well where we stand now is the new version of the technology is in beta test versions. We got it into the hands of people who had used the technology before. So there are NFL teams that are using, there are college teams, there's Olympics, there's the Navy SEALs, Major League Baseball, the NBA, the National Tennis Association. They have locations where now they are trying this out and reporting back. How's it working? How could you change it? How could you improve it?

Andrew Huberman:

Great.

Craig Heller:

And so forth. So that's where we are. But on the website, you can actually sign up for being one who will be able to get one when they are finally manufactured. They're now being made in fairly small lots because you want to change things as you realize how it can be improved.

Andrew Huberman:

Yeah. This is Stanford, after all. You want to get the technology right. I like to joke that one of the reasons I like being at Stanford so much is that not only are my colleagues amazing and they're so forward thinking, but they're all perfectionists. And so the perfectionist mindset is it has to be perfect before it can go live, so to speak. Well, I think there will be a lot of interest. Let's talk about the technology in a little more detail for a moment. And then let's talk about whether or not crude forms of that technology exist. Either for sake of safety and/or performance.

Andrew Huberman:

The CoolMitt, as I understand, is, it's a mitt, it's a glove.

Craig Heller:

Yeah.

Andrew Huberman:

You put your hand into it, you hold onto a surface and that surface cools your hand, and thereby, through this specialized portal, cools your core body temperature and all the muscles of the body. Subjectively, if I were to do this right now, would I think that it was ice cold or would I think it was just cool?

Craig Heller:

Just cool.

Andrew Huberman:

I see.

Craig Heller:

Ice cold is too cold. So people always ask, "Well, why can't you just stick your hand in a bucket of ice water?" It's too cold. What that does is that causes reflex vasoconstriction of the very portals that you're trying to maximize the heat loss from. So you stick your hand in cold water; when it comes out, it's cold.

Andrew Huberman:

You just sealed up all the heat in your body.

Craig Heller:

Yeah, right. So well, what I recommended to someone at one point. They said, "Well, when I'm running, can't I just carry a frozen juice can and it will gradually melt?" And I said, "Well no, because that's going to decrease the heat loss from that hand. But if every couple minutes you switched hands, it might work.

Andrew Huberman:

Exactly. Well, I have a feeling that there are people now doing that as well as trying this. So how long in the CoolMitt; at the proper temperature, how long are people putting their hands into the mitt?

Craig Heller:

Well, we once again had just standardized on three minutes. And part of the reason for that is that the rate of heat loss is an exponentially declining curve. And three minutes gets the best part of the curve. So you can go longer and get more benefit, but the biggest bang for the buck is in the first two, three minutes.

Andrew Huberman:

Okay. You mentioned a number of impressive organizations, sports teams and military that are using this. This is not something that I typically see on the sidelines of games, although to be honest, I haven't looked very carefully. I'm guessing that they are probably keeping the technology somewhat under wraps. Where and how are they doing this? Are they running back to the locker room? I mean, the military special operators are doing their thing, but in terms of the athletes, is it possible hypothetically the athletes are doing this somewhat incognito?

Craig Heller:

It's possible, but I really don't know. People have mentioned here at Stanford, they don't see the football team using it. Well, the football team here at Stanford is mostly playing in cold weather. Cool weather. The night games are cool. Even date games are not very hot frequently here. But when they go to a hot place like Arizona or Utah, at least our coach, Shaw, says that they take it with them, and that's when they find the benefit. That's when they use it.

Andrew Huberman:

Interesting. So is there a poor person's, poor man or woman

Andrew Huberman:

A poor person's, poor man or woman's version of this. You mentioned the juice can passing back and forth. You mentioned cooling the hands. A number of people said to me after learning a little bit about this science and technology that they've experienced some big effects, positive effects of cooling by ... and I confess, I've done this. Taking a package of frozen blueberries and just kind of passing it back and forth between my hands. Now talking to you, I realize I probably didn't do it long enough. I was only doing maybe 30 seconds, passing it back and forth between my hands and then going back into sets. I did see a performance-enhancing effect. Absolutely. But I realized I probably wasn't optimizing the protocol. If you were going to give a crude protocol, let's just say, for the gym, because with running it's a little bit tricky, but what would that look like if people wanted to just play with this in some sort of fashion?

PART 2 OF 4 ENDS [00:54:04]

Craig Heller:

Well, it would be experimental.

Andrew Huberman:

Sure. Yeah. None of that is kind of very controlled.

Craig Heller:

Your idea of frozen peas is a good idea. And I think since there's been no actual study of that, you would have to be ... you working out, what is the best for you? But one way to figure it out is that if after you hold the cold peas in one hand, then you switch it to the other hand, if someone then comes and feels your hand, is it warm or cold? If it's cold, it means you vasoconstricted. If it's warm, it means the hot blood is still going there. So we do that in the lab.

Andrew Huberman:

And the key is for it to not vasoconstrict.

Craig Heller:

Right.

Andrew Huberman:

Okay. So there's a test out there, folks. If you're going to try this in kind of a crude fashion, at least until the CoolMitt is available more broadly to the general public, you want to assess whether or not your palms actually feel cool to the touch by somebody else ... And if it does, that means you've essentially shut down the port, or you're sealing in more heat, which is bad. What about putting this cold pack of some sort on the face ...

Craig Heller:

Or the feet.

Andrew Huberman:

Or the feet. I work out at home. I don't often work out barefooted, but I suppose I could, like they did in the '70s, when those guys were walking around without shoes and squatting without any shoes or socks on. Could I put my feet on them?

Craig Heller:

You could. If you simply had a water-perfused pad and you were circulating cool water through it, you could just put your feet on it. Okay? Part of the problem is that you don't want ... Let's say you have just a cold pack of something. The problem is back to boundary layers again. If you don't have a convective stream of the cooling medium, the heat sink is not as effective, because there'll be a boundary layer developed between the heat sink material and your skin. So that decreases its efficacy.

Andrew Huberman:

I see. Maybe we should just, for a moment, talk about convection, radiation and convection, and just make that clear. If I put my hands ... Let's say it's a cold night and I'm at a campfire, and I take my hands and I put them out to the fire.

Craig Heller:

You're getting radiation.

Andrew Huberman:

You're getting radiation. Okay. And then if it's a windy, warm night ... No, I don't know if that's the best example. Give us a good example of convection.

Craig Heller:

Convection, sure, is in a cool breeze. The wind chill factor, that's due to convection. But in terms of heat transfer between two objects, if you have convection of the medium, whether it's blood on the inside and water on the outside, you increase the heat exchange if you have convection on both sides.

Andrew Huberman:

Right. So this is why just planting my bare feet on two packages of frozen peas, there's really no opportunity for circulation and therefore heat transfer. So it's not really optimal, which is ...

Craig Heller:

But once again, it depends on the surface area to get any benefit at all. We have a study that we published, which was investigating the standard treatment for hyperthermia in the field. And the standard treatment that's recommended by medical organizations is you take cold packs, and you put them in the axilla, the groin.

Andrew Huberman:

The axilla are the armpits.

Craig Heller:

The armpits, yeah. The groin, which is a ...

Andrew Huberman:

Thin skin, lots of vasculature.

Craig Heller:

Right. And the neck. So what we did is we did studies in which we made people hyperthermic, and then we measured the rate at which we could cool them by putting those positions, those heat exchange bags in the recommended location versus on the glabrous skin — versus palms, soles and face. The cooling rate was double if we put the same ice packs, the same cold packs on the heat portals rather than the axilla, the groin and the face or the neck.

Andrew Huberman:

Wow. So face, hands and bottoms of feet will cool you twice as fast as putting cold packs into your armpits, your groin or back of neck.

Craig Heller:

So I like to give the analogy of if your car is overheating, okay, and you have a hose, a garden hose, where should you spray your cooling system? Should you spray the radiator, or should you spray the tubes going in and out of the radiator? Well, the rationale with putting these cold packs in the axilla, the groin and the neck is that you're getting close to the major arteries. Sure, that's going to be effective, but it's much more effective if you actually increase the heat-loss capacity of the radiating surface, the radiators.

Andrew Huberman:

So you cool the hot stuff heading toward the core.

Craig Heller:

That's essentially what the standard operating procedure is, that you hit the arteries.

Andrew Huberman:

Amazing.

Craig Heller:

And the veins — the arteries and veins.

Andrew Huberman:

I'm going to just tell a brief story that illustrates how almost everybody gets this stuff wrong, and then I'm going to use that as an opportunity to ask you about heating, deliberate heating, as opposed to deliberate cooling. So about four months ago, a friend of mine, incidentally a guy who did nine years on the SEAL Team, is a really skilled cold water swimmer. We went out for a swim in the morning. I'm not nearly even close to being in the same universe of his output potential. We do these swims. I'm familiar with them. I got enough blubber on me that I stay warm enough in the cold Pacific, no wetsuits. We do the morning cold swim for about a mile or so. And we brought with us a young kid that I know real well that hangs out with us sometimes and trains with us who's got very little body fat.

Andrew Huberman:

He's just exceptionally lean despite eating everything in sight. Right? Teenager, great athlete, great kid, great swimmer. So we're out there swimming, and at some point we're talking to him, and it's clear that he's gone hypothermic. He's slurring his words. He's not doing well. So we get him onto the beach. His teeth are turning yellow. He's quaking, he's not ... His saliva is taking on that consistency that's clear, like he's hypothermic. We go to the lifeguard station. Lifeguard says, "Okay, let's get his vitals. Let's do all this." Meanwhile, trying to stand next to him and heat him up by heating up his torso. So there we are pressing against this guy, our friend, trying to heat him up. They get a blanket on him. I'm realizing he was barefoot. His face was exposed. Although we did cover his head with the blanket, and he eventually came back. We got some warm liquids into him, and he was okay. He was fine.

Andrew Huberman:

I don't know that his mother is ever going to let him swim with us again. If I ever disappear or go missing, it's because of that incident. Anyway, he did great. He recovered. He's back in the water and doing well. But I realized that pretty much everything from the point where we got back on the beach until he was back to normal was, we did incorrectly. We heated his torso, we left his extremities exposed, and we assumed we were doing the right thing. And the lifeguard is a skilled lifeguard at a major public beach. So I guess the simple question is, did we get everything wrong? Did we get anything right? And what would've been the better option to heat up a hypothermic person in that or a similar situation?

Craig Heller:

Well, it's interesting you asked that because that is the way we got into this area of investigation. I worked on how the hypothalamus regulates body temperature, neurophysiology. And one day we were having a discussion with a colleague in the Department of Anesthesia, and he jokingly said to my colleague, he said, "Yeah, you guys think you know so much about temperature. I bet you couldn't solve a problem we have in the recovery room." "What's that?" "Well, the patients come out of surgery. They're hypothermic, and it takes us hours to get them to stop shivering." What do they do in the recovery room? Exactly what you suggested. They put on warm blankets. They put on heat lamps, and it takes them an hour or two hours to get these patients to stop shivering, to bring them back up to ... So we say, "Ah, it's a trivial problem." No, it's a heart problem.

Craig Heller:

It's a heart problem because when you're under anesthesia, you're vasodilated. When you come out of anesthesia, you're hypothermic and you vasoconstrict. That makes it very difficult to get heat into the body. So we got the idea that, well, if we could just take one appendage, like an arm, and we put it in an environment wrapped in a heating pad and a negative pressure, suction, that would pull more blood into that limb, that blood would get heated and it would warm the body up faster. So my colleague built a prototype device. You couldn't get such a device into the hospital these days, but we were with our anesthesiologist friend. We took it into the recovery room, and first thing that patient said, "No way. You're not going to put that on my patient." But he prevailed and first patient didn't shiver at all. First patient was back to normal temperature, core temperature in, I think it was eight minutes. Eight or nine minutes.

Andrew Huberman:

Is this now standard practice in hospitals?

Craig Heller:

No, no, no. No, no, no.

Andrew Huberman:

So this is another example where I don't get upset about the ... although it's upsetting to know that it's not. But I think that it's yet another case where a fundamental problem exists. There's a science-based solution that makes sense at the level of physiology, engineering and practice, and yet it's not being done. And I mean, that's a whole other discussion as to what the limitations are. Well, perhaps, I know a number of our listeners are in the healthcare and medical profession as well as military, athletes, and just also standard other types of jobs, civilians doing other types of work. It would be wonderful if people understood this. So once again, is there a homegrown technology that people could use? If somebody's hypothermic, what is going to be the best way for them to warm up? Is it going to be holding a nice warm mug of cocoa, or something like that? But not too hot, I guess is, again, the idea.

Craig Heller:

Yeah. Well, actually you can go hotter on the glabrous skin.

Andrew Huberman:

Oh, because it'll dilate.

Craig Heller:

Because it takes the heat away faster. But back to the anesthesia, what you can do is you can use warm pads. They have them in all hospitals. They have circulating water-perfused pads.

Andrew Huberman:

Hot water bottle type stuff.

Craig Heller:

Put them on the feet.

Andrew Huberman:

So typically they'll slide them under your lower back, or something like that.

Craig Heller:

Yeah. Put them on the feet. Okay, sure. That will do it. But turns out that we discovered through this work that it had nothing to do with the whole arm. It was only the hand. And that's when we came to the realization of these special blood vessels. We didn't discover the blood vessels. They're described in "Gray's Anatomy," but nobody knew what they were for.

Andrew Huberman:

And you mentioned bears earlier, and other hairy animals. Do they have these AVAs as well?

Craig Heller:

Oh, yeah.

Andrew Huberman:

And I suppose we haven't defined AVAs. We've been pretty good about the no acronyms rule. AVAs is ...

Craig Heller:

Arteriovenous anastomoses. So a connection between the arteries and the veins. Yeah.

Andrew Huberman:

I actually use this technology. I have a bulldog, bulldog mastiff. He has a very high propensity for overheating because they're terrible at dumping heat. And bulldogs are great at pushing themselves to the point of exhaustion or death. It happens. And so now we do what we call palmar cooling. Sorry, I couldn't help myself, where I'll take Costello and lower him into a cool body of water, just the bottoms of his paws. Although I think animals instinctually know to do this and will go and stand in bodies of water. They don't often lie down all the way. Some do. But they seem to know that's a great way to cool themselves off.

Craig Heller:

Yeah. Oh, absolutely. Yeah.

Andrew Huberman:

And they get the advantage that their palms and their feet are essentially the same thing.

Craig Heller:

We actually built devices for dogs.

Andrew Huberman:

Did you really?

Craig Heller:

And tried them on. Iditarod sled dogs, and it worked beautifully. They had little backpacks with the equipment and pads on all their feet, and it worked beautifully.

Andrew Huberman:

Amazing. Amazing. Along the lines of heating, deliberate heating, wearing a knit cap is something that — you see more of that on the East Coast. People run around Boston and New England with a knit cap. I've always done that at the start of my runs to try and warm up more quickly, and then I take it off. I shed layers as I go. Is that a rational practice, the way I just described it?

Craig Heller:

Oh, sure.

Andrew Huberman:

Yeah. Because warming up is important too. There's a certain amount of quote unquote "warming up" that's required to lubricate joints, or at least to get the sense that joints are lubricated, and to be able to move more easily. Do you still recommend that people warm up?

Craig Heller:

Yeah. But I think we're misled by the term "warm up," as if the major purpose is to raise temperature. I'm not aware of any data on this, but I do think that the major contribution is increasing flexibility. So you're going to avoid having damage of joints and tendons and ligaments and so forth. But also the ability of the mitochondria to produce energy can be impaired at lower temperatures. And you have to keep in mind that we say our body temperature's 37 degrees, but that's not true.

Andrew Huberman:

Yeah. It varies across the day.

Craig Heller:

Well, it varies in parts of your body. I mean, my hands and arms are not at 37 degrees right now. They're much lower.

Andrew Huberman:

So that raises an interesting question. What is the best way to measure core body temperature?

Craig Heller:

Well, the best core temperature is, what we use is esophageal. So we put a thermocouple up the nose, about two feet down the esophagus so that it's about the level of your heart.

Andrew Huberman:

Not gym or home practical, although I don't know. Some of those COVID swab tests go pretty far. I can't even imagine going any further. I felt like my brain was getting tickled, and it really wasn't.

Craig Heller:

But tympanic is a pretty good-

Andrew Huberman:

So the ear?

Craig Heller:

The ear. It's not foolproof because you have to actually have it aimed properly at the tympanum. And frequently what you're getting is you're getting sort of a mixture of tympanic plus ear canal temperature.

Andrew Huberman:

And for those listening and for those watching, the tympanic is not going to be the pinna, that this part of the ear, the outer part of the ear. The tympanic is going to be near the ... headed towards the tympanic membrane. And yes, I'm sticking my finger in my ear because that's where the laser would actually have to go to measure your temperature. So when we're walking into restaurants and other places nowadays, and they're shining the laser at our forehead, that's probably giving a pretty crude readout of temperature.

Craig Heller:

It is, but there's much less insulation between your brain and your forehead skin than there is between your biceps and your arm skin. So if you're going to measure a surface temperature, that's where you would do it. And we do temperatures in the infrared. We take infrared videos of athletes and our subjects, and of course, the face lights up.

Andrew Huberman:

Okay. So if we're not ... I imagine there's going to be a technology coming soon where you can point your smartwatch or your smartphone at yourself, and you're going to get a heat map. If somebody out there hasn't already invented this, for the typical folks outside military, somebody please invent that because I think there's growing interest in temperature, based on the work that you're doing. And also for sake of something I do want to touch on, which is sleep and metabolism, although we don't want to open up those portals all the way because we'd need several days to cover it. Okay. So putting on the cap, what about some of the helmets and gloves that are used in typical sports? Do you think that those can be improved in order to improve performance in terms of their ventilation ability or keeping palmar surfaces open, for instance?

Craig Heller:

Well, you mentioned about the knit cap in cold weather, especially, and that is significant because you do lose a lot of heat from your head, but it's a constant heat loss. It's not variable like your glabrous skin. So if you decrease that heat loss, you're going to be warmer. So sure, that has an impact. Now, in terms of helmets, they should be ventilated. I mean, they should have enough space in them and holes in them so that air can circulate. You don't want to insulate, thermally insulate your scalp. That's going to decrease heat loss quite considerably. Just for a resting individual, the brain is about 20% of your metabolism. So that's a lot of heat production.

Andrew Huberman:

Yeah, absolutely. I realized there was a question that I failed to ask earlier that is burning in my mind now, and I think is likely burning in the minds of some of the listeners, which is, So if you do this cooling in between sets in the gym, you get this performance-enhancing effect. You don't get the delayed onset muscle soreness, which is great. So presumably the body is adapting. You're getting better as a consequence of being able to do more work per unit time or to go harder in some way. You get that adaptation. Does that mean that you see a performance-enhancing effect even when you don't cool if you've previously done the cooling workouts?

Craig Heller:

Yes.

Andrew Huberman:

So for instance, let's say I can do 10 sets of 10 dips, which I like to think I can. Maybe I need to go try. I don't know if I've done that recently. I do the cooling. I cool for three minutes between sets, and let's say I get to the point where I can do 20 for 10 sets, 10 sets of 20 repetitions, and then I don't cool. Will I be able to match or approximate my new better performance?

Craig Heller:

You keep your gains. It's a true conditioning effect. You respond to the increased work volume by all of those mechanisms you mentioned. You increase the number of contractile elements in your muscles. Muscles get bigger. We had an experiment that involved some of our female students, not athletes, but just regular. They were freshmen, actually. And the experiment was 10 sets of pushups to muscle failure, with or without cooling.

Andrew Huberman:

Same regimen, three minutes of cooling in between sets of pushups.

Craig Heller:

Right. Some of those young ladies reached over 800 pushups.

Andrew Huberman:

Now, the total duration of the workout could be getting much longer as a consequence of doing more work.

Craig Heller:

No, no, no. It doesn't take you longer. Well, minor. I mean, a pushup is pretty fast.

Andrew Huberman:

Yes. Pretty fast.

Craig Heller:

So you do 10 sets, the maximum, 45 minutes total.

Andrew Huberman:

That's a lot of pushups.

Craig Heller:

That's a lot of pushups. And so the interesting thing is they came in one day and they said, "Dr. Heller, you cost us a lot of money." "Why?" "Well, we had a formal dance this weekend. We all had to buy new sleeveless dresses."

Andrew Huberman:

Nice. It's a good problem to have. Good problem to have. Let's talk about steroids, anabolic steroids. We're heading into an Olympics. Every time the Olympics rolls around, you hear about these cases of people getting "popped," as they call it, or caught for anabolic steroids. There's some accusations out there now; there'll be more. This will get handled in the press and then in the various organizations. Clearly athletes and nonathletes use anabolic steroids. And typically anabolic steroids are of the testosterone variety. There are derivatives, et cetera. And those derivatives do different things, and anabolic versus androgenic, et cetera. But typically, the idea is, as least as I understand it in talking to some of these individuals, is that they allow people to train more because they recover faster. They are able to synthesize more protein because they're basically getting a second puberty. Because as we all know, during puberty, there's a lot of growth of the body.

Andrew Huberman:

And of course there are a lot of negative effects of abuse of these things, and they are banned from various sports organizations. Especially, I should mention, in combat sports. This is especially concerning because in combat sports, a performance-enhancement means that you can harm somebody more than you would be able to otherwise, as opposed to in other sorts of sports. Just to conceptualize it, and I'm not taking a moral stance on any of this, I just want to ask you, when you compare palmar cooling to anabolic steroids in terms of gym performance, what do you see?

Craig Heller:

Well, we do not do research on steroids, but there is a lot of research in the literature. A lot of that research in the strength conditioning magazines, it's not very scientific.

Andrew Huberman:

No.

Craig Heller:

Okay.

Andrew Huberman:

Or it might not even be scientific at all.

Craig Heller:

Right.

Andrew Huberman:

Right.

Craig Heller: